Alhaji Kola Animasaun: An icon still missed six years after

By BASHIR ADEFAKA

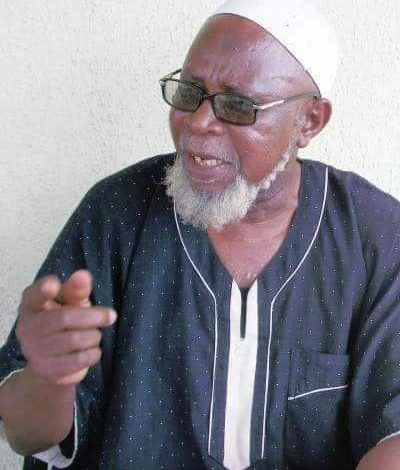

Today in history, May 30, 2019, Alhaji Kolawole Muslim Animasaun finished work and had since returned to his Lord. Although Islam approves only three days for mourning the dead, six years after his demise, I particularly still miss him, a father in a million. He was a great man.

Popularly addressed Alhaji Kola Animasaun, the author of widely read Voice of Reason, a Vanguard column, and the newspaper’ former Chairman Editorial Board left behind a yet to be filled vacuum. He was extremely good and fantastically a noiseless philanthropist. A great teacher of moral and good character, Daddy lived his life as an excellent contributor of opportunities through which many young Nigerians, including me, had grown.

Although his absence continues to push my heart through painful experience of life, especially now, my consolation is in the fact that Dad left behind a family of good minds like Alhaja Siliphat Modupe Animasaun Knee Ajimobi – widow, and children whose characters, generally, are in no departure from his. Jannat al-Furdaus fil Akhira for Dad, Inshallah!

In celebrating him today, I simply lift a Vanguard’s report of review of his “1939: Autobiography” by Mr. Steve Ayorinde, then MD/Editor-in-Chief of National Mirror, which he did on July 5, 2012 at the book’s public presentation, held at the Nigeria Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), Victoria Island, Lagos, coinciding with his 73rd birthday, as published by Vanguard of July 8, 2012. Excerpts:

From 1939 to the vanguard of modern journalism: The story of a Musulumi

And for a man who clocks 73 today, more than 40 years of which he spent in active journalism, there is indeed a lot to say about life, the media profession and, interestingly, about how the practice of it connects with the political trajectory of the nation.

1939: An autobiography – Kola Muslim Animasaun; Tellettes Consulting Coy Ltd, 2012. Pp: 205

Reviewer: Steve Ayorinde, MD/Editor-in-Chief, National Mirror

Considering the central, even towering, role that journalists play in shaping the thoughts and perception of a nation, it often makes sense to acknowledge their contribution to national discourse whenever it comes in form of a book. For journalists who are blessed with long lives and remarkable careers in particular, the tendency to make their narratives the barometer for measuring the nation’s pulse is very high.

Alhaji Kola Animasaun’s autobiography falls within the category of memoirs that fulfil the requirement of literarily killing two birds with one stone – that is, telling the story of his own life and that of the larger professional and political environment around him in a complimentary, easy-to-read manner.

And for a man who clocks 73 today, more than 40 years of which he spent in active journalism, there is indeed a lot to say about life, the media profession and, interestingly, about how the practice of it connects with the political trajectory of the nation.

Whether it is called 1939 or aesthetically referred to as 1 thousand 9 hundred and thirty 9, the title of Alhaji Animasaun’s book is very functional in using the date of his birth as the pathway into a telling testimony of a life worth recollecting. And there is no pun intended in his choice of word as the book’s functionality is not limited to the aesthetic lustre of its title or in the silhouetted, artistic impression of the author on the cover of the book alone. The form and content of the 205-page book attest to the author’s firm control of the art of storytelling; lucid, even-paced and witty, all signposting an abundant capacity for effective narration.

Divided into nine broad chapters, with additional shorter writings from previous articles penned under different pseudonyms, in the annexes, 1939 appeals to a reader that is interested in the Kola Animasaun persona – as a journalist and writer of note; as a contented family man unabashedly devoted to Almighty Allah and as a man whose ideological convictions might be modest, but are nevertheless duly advertised as a Progressive.

But it is the professional persona of the author that resonates throughout the book, leaving no surprises as to why the opening chapter, aptly titled Back to Front and the closing chapter, Drawing the Curtain: Front Cover, perform two main functions – to celebrate him as an accomplished media professional and perhaps, more importantly, to acknowledge a number of people and institutions to whom he owes a debt of gratitude.

The Vanguard newspaper where Alhaji Animasaun worked for 19 solid years, as the culmination of a career that took him to different parts of the world – as a student, professional and a devoted Muslim – expectedly gets a fair share of mention in the book. More importantly is the honour accorded an icon of the profession and the publisher of Vanguard, Mr. Samson Oruru Amuka Pemu, as the man whom the author celebrates more than others being the person used by the Almighty Allah to give his career the needed fillip.

And there is a unique style, with a tinge of humour and camaraderie, to how Alhaji Animasaun writes about people he holds in high esteem, whether they are friends and benefactors like Uncle Sam Amuka, Akirogun Segun Osoba and the Sultan of Sokoto, His Eminence, Alhaji Mohammed Sa’ad Abubakar 111; or even the woman he describes as his own ‘jewel of inestimable value’, his wife and mother of his seven children, Modupe.

From left: Oba Adedayo Olaloko Shobekun, Alhaji Kola Animasaun, and Engr Abiodun Adenekan, during the public presentation/ launching of the Voice of Reason Volume 2, by Alhaji Kola Animasaun, in Lagos. Photo: Kehinde Gbadamosi

On the man whose name is now synonymous with Vanguard newspaper, the author has this to say: “Uncle Sam has been most generous to me…in 19 years of work, he was angry with me, not directly, only once…even when I got him angry with my columns, he would call me as he did on an occasion: ‘you are costing me some of my friends’, he would quietly lament.”

But in eulogising the publisher of Vanguard newspaper, the author has also thrown a subtle challenge at Uncle Sam himself and the entire Vanguard family, just the same way that Chief Osoba did a few months ago at the launch of his biography – The Newspaper Years, that at 77, not only is Uncle Sam the oldest practising media professional in Nigeria today but is also undoubtedly the most celebrated. This fact, therefore, calls forth the need for the Sam Amuka book, either in form of a memoir or a biographical account from a gifted insider. But I do not wish to digress.

In dissecting the Kola Animasaun years in active journalism, from his youthful days as a sub-editor in Daily Express to his cub reportorial days in Tribune and ultimately to the unforgettable years in Vanguard, where the author worked in various capacities as the Chief Sub-Editor and Chairman, Editorial Board, the reader comes in contact so intimately with the renaissance years of contemporary journalism in Nigeria.

The reader will see through the eyes of the author the hurdles and challenges associated with the profession, the fame and the opportunities as well as the politics of it. An example of the latter was how the author initially lost a plum job at the Sketch to his friend and junior colleague, Peter Ajayi.

The good old days come with clear recollection by the author and the reason for devoting a great deal to people that added value to his life becomes apparent. The author reveals himself as a product of referrals – combining his qualifications and skills with pedigree and social contacts in climbing the ladder of success.

From the early days with Chief Bisi Onabanjo to Chief Olu Adebanjo, Chief Dapo Fatogun, Dapo Fafiade (Don Nugotaf), Alhaji Ganiyu Akintola-Bello, Alhaji Lateef Teniola (Dan Newsman), S. B Osunlolu (ESSBEE) and Chief Eddie Aderinokun, who wrote the book’s foreword, the author nurses fond memories of his formative years on the job. Those were the days when all he wanted to be was a sub-editor: “It is still a job I love to do,” he writes on page 32. “To give character to a story; it is like dressing up a mannequin. You highlight the selling points. Nothing can be more pleasing to an artiste more than that.”

But he is not the type that is all wrapped up in self-adulation. He uses kind words in appreciating other writers dear to him like Chris Okojie, Doyin Omololu, the late Hakeem Ikandu, Bisi Lawrence, Pini Jason, Dele Sobowale and Gbenga Adefaye to mention but a few. Notably, for a journalist who reported the political upheavals of the post-independence era and was involved in the media machinery deployed during the Nigerian civil war, it would be near impossible to remain ideologically and politically neutral, even while maintaining a semblance of balance and fairness.

Right from the beginning, the author pitched his tent with Awoism and has consistently aligned with those he considered to be progressives – from Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s Action Group and Unity Party of Nigeria, to the short-lived Social Democratic Party of the third republic and subsequently metamorphosing ideologically with the Alliance for Democracy and Action Congress to the present Action Congress of Nigeria, Alhaji Animasaun has not seen the need to change his position.

But he has a word of caution for those directly in the fold, according to him: “True you cannot make out the progressive policies anymore today but hope they will show the promise to the old slogan: Vita Plenor et Liberta Omnibus – Freedom for all; Life more abundant!”

Today’s eagle-eyed professionals who sometime reckon that journalism is but a springboard to the political arena will find the author’s foray outside of journalism profession instructive. Whether in the corporate world, diplomatic service or politics, Alhaji Animasaun often learned the hard way – that considerations other than merit tend to determine how you measure on the ladder of success.

He first learnt that as an Officer at the Ministry of Information where boredom nearly killed him. “You had to be inventive not to lose your mind,” he declared. “So you find the creative ones writing plays, or acting them or writing novels.” It was hardly better when he got posted to the National Provident Fund (NPF) as its Public Relations Officer. His experience there on account of workers protesting over benefits was a stuff made for live theatre.

He writes: “The NPF office on Broad Street then was like a war front. There were shouting bouts and actual fisticuffs. It was not unusual to find people come to the office with juju or deadly reputation – Epe, Afose and gbetugbetu.”

Where people didn’t resort to black magic to register their grievance, they simply resorted to character assassination in form of letters and petition as Alhaji Animasaun would later experience when he served as a caretaker chairman of Abeokuta North Local Government.

It was a perplexed Animasaun that declared in the book: “I have never been in a more thankless job…they would come for all sorts of assistance that are not provided for in the budget. Those who would want the antenatal bills of their wives settled would come; those who would want to bury their newly dead parents or relations or re-bury their long dead relations made routine calls.”

In frustration he tried to resign the post by sending his resignation through the deputy governor, Alhaji Gbenga Kaka. But his friend, the governor, Chief Osoba, from whom he had accepted the invitation to serve, would have nothing of such. “He told me I should take the challenges and not run away”, the author recalls.

Although he lived the life of a nomad while growing up and had fond memories of Ibadan where he got his wife, a job and a rich immersion into the world of arts and literati that was the hallmark of the city in the 1960s, the author is unequivocal in highlighting his Islamic and Abeokuta heritage, as succinctly captured in Chapter 5.

He was named after a fearless Islamic scholar, Alfa Musulumi Dindi, the revered Mallam of Abeokuta. And he carried the Islamic toga with him for some time, particularly when he first arrived in London as a student, when it was said of him in the Nigerian communities that omo Alhaja mura bi Alfa – meaning Alhaja’s son is dressed like an Islamic scholar.

If he had acted fearless as a commentator on the ills of certain Nigerians going on hajj for unholy purposes like drugs, theft and prostitution; or acting in a principled way as to initially reject the title of Alhaji, because he argued that you could not be an Alhaji again once you have returned to your country from the pilgrimage, it is because Kola Animasaun is just being true to his name – Musulumi – and the fearless but godly man he was named after.

But this author is also a pragmatist. No undue pretences. When Nigerians, almost always given to titles and fanciful accolades, insisted in referring to him as an Alhaji, he simply allowed them. Also, he realised in no time during the 1960 Independence euphoria among the newly educated who subscribed to Marxism and Socialism that “ideologies soon wear thin where the stomach is empty…”

But religion and social ideologies aside, he is also alive to his roots and would spare no detail in narrating how he traced a part of his roots to Omu Aran in present day Kwara State. All through his odyssey, a noticeable tread of modesty and decorum runs through. But those are values borne out of good upbringing than social denials.

His background was middle class and unlike those who ride on their days of little beginnings and lack of shoes to gain popularity and power, Kola Animasaun had enough shoes while growing up; he was indeed trendy and fashion conscious. He recalls with nostalgia how he got the nickname of Anny Wool because woollen material was in vogue and he had them in all textures and description.

Except in few areas, one is not likely to call to question the editing in this book, the only glaring exception being on page 32 when July 30, 1988 was recorded as the date when the author approached Uncle Sam Amuka for job- hunting, when in fact it happened three years earlier in 1985 as recorded in previous and subsequent pages. The printer’s devil also reared its head more than once in the captioning of the photographs.

But by far the most exasperating as a drawback, aside the absence of an index, is the persistent non-separation of words on several pages. This, one guesses, must have happened at the printing level. But all these hardly detract from the import of this well-written and absorbing memoir.

In concluding, therefore, the book succeeds in establishing that in a materialistic era where everything has become fast, fierce and dangerously competitive, not many people would declare as the author has done that he has never been ambitious but has been happy to take whatever comes to him with gratitude. 1939 essentially reveals a contented and fulfilled man.

Yet, by far the most remarkable summation for the book appears in the last paragraph of the first chapter where the author declares with a heart full of thanks: “19 years in Vanguard had been the crowning glory of my career. A substantial population of educated Nigerians know me or have heard about me. All thanks to Allah, Uncle Sam and Vanguard.”

This is Alhaji Kola Muslim Animasaun at his most heartfelt; and this, indeed, is the thrust of 1939 – the book.

I thank you all for listening.

May Allah repose his soul in Al-Jannah Firdaus, Amiin.