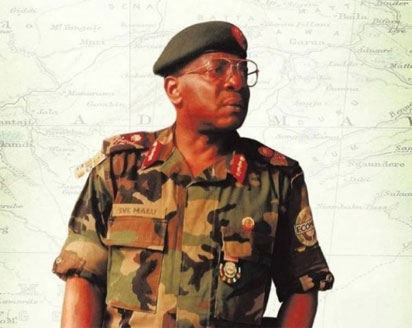

General Victor Malu: A life of spectacular ironies, by Dr. Ugoji Egbujo

Malu, the General, is dead. He won many battles but succumbed to diabetes at 70. Reputed for hard work and professionalism, Malu was the ideal soldier. He went into the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) when military fervour was at its peak, in 1967. He was commissioned in 1970. Biafra had surrendered. But life had other battles lined up for him.

The first test came early. Six years after he was commissioned, he was arrested and investigated for coup plotting. Bukar Suka Dimka had executed Gen Murtala Mohammed. He was exonerated, set free, after two weeks. A member of the legendary NDA’s 3rd regular course.

His course mates held the reins of succeeding juntas after the military returned to power in 1983. David Mark, Tunji Olurin, Chris Garuba, Mike Akhigbe, Haliru Akilu, Raji Rasaki, Abdulkareem Adisa. They were everywhere. Malu was in literal oblivion. 1999 came. Democracy made a return. Military Officers that had held political positions were deemed too ambitious. Malu was celibate, and given the reins of the army.

Before then, in 1996, he commanded ECOMOG forces. He turned the fortunes of that sub-regional peace force around. But even the stint at ECOMOG didn’t go without a riddle. While he was drenched in global applause for diligence and professionalism , Liberia’s Charles Taylor found him uncontrollable. His ECOMOG tour of duty was therefore cut short. In his farewell speech he lamented his sudden exit. He told the soldiers to maintain a ruthless streak.

While at ECOMOG he was handed a case to decide at home. He chaired the military tribunal that tried General Diya and others for involvement in an alleged coup plot against General Abacha. Many believed Diya’s coup was a phantom. Malu found Diya and others guilty. Malu could not exonerate Gen Diya. Many believed that despite his reputation for brutal frankness he was timid in front of Abacha.

If fate played funny games with the late General, it saved the best for the last. It dished him cruel cards. The first term of the Obasanjo’s administration.

There was Odi. Elections were over, Aswana boys ( local thugs) felt used, and dumped. They threw tantrums at ‘ungrateful’ politicians. Police were called in to restore public peace. The boys were dislodged from their Yenogoa Black Market domain , in a heavy handed operation. Those who didn’t die shifted their camp to Odi. Their nuisance grew, and became great.

The Police had it rough going. Seven policemen were abducted in Odi. Then another five. They were all slaughtered. Then president Obasanjo gave the governor two weeks to fish out the culprits. He forgot who was the Commander in Chief of the Police. He brandished threat of declaration of state of emergency. Two weeks! he said. Before two weeks, and while the community fretted over promised drastic consequences, the Army moved in. The Army sat on Odi for two weeks. And Odi was decimated.

Everything was razed. They left only the bank, the health centre and the church. Malu was Chief of army staff. His idea was that Odi had to be taught a brutal deterrent lesson. Odi was made a lesson. But it would seem some soldiers learnt a thing about barbarity too. That was 2009, November.

In 2011, Malu fell out of favour with his Commander-in-chief. He was removed from his position and retired from the army. A few months later fate came with its mischief. That was the season of the TIV- JUKUN ethnic madness. The Army was sent to Ibi in Benue to patrol the area. Ethnic tension had squashed peace. They fell into an ambush laid by Tiv ethnic militants. Desperate efforts were made to get them released. The soldiers were killed in a school in Zaki Ibiam, the next day. The governor cried mistaken identity. What followed was truly gory.

The army was sent in. They were sent to fish out the criminals. They came like peace makers. They gave the villages a notice . They said they wanted a peace meeting. They chose a market day. So that they would have a full house. On the appointed day, the Army in Abuja was busy burying their dead with national honors. That day, the army in Benue descended on a number of villages.

They started with Gbeji. Everyone gathered as appointed. Women and children were separated from the men. The men were sprayed with bullets. Everything that moved was shot. Everything that stood was brought down. They burnt dead bodies for fun. They burnt empty homes like pyromaniacs. Everywhere, they went arson followed them. And they went around.

They got to General Malu’s country home in neighbouring Katsina Ala. They burnt it. Three of his close relatives were killed, in his compound. A community that took pride in having a soldier in every family lay in waste. Desolate, charred, ravaged by their army’s ruthless reprisals. Vaase, Gbeji, Kastina Ala, Zaki Ibiam, nothing was spared. Malu, as chief of army staff, stood against proposed American modernization of the army. Malu, the retired General bore, the brunt of Army’s crudity. General Malu grieved in plain sight. He lamented that only the army could have been that brutal.

The corpse of a stranger, they say, feels like a stack of woods, evokes no grief. Odi didn’t teach him what Zaki Ibiam taught him. We wouldn’t know all his other regrets. We know he was strict and disciplined. He left an autobiography. He titled it—In the name of Victor: confronting errors with truth. We can’t tell how much of Gen Abacha’s errors he confronted with truth. But it was Gen Malu who shocked others when he wore Abacha’s badge on his military uniform. We wouldn’t know whether he came to regret that.

He didn’t regret convicting Diya. We know he served his fatherland diligently, and died in an Egyptian hospital. Even that would elicit another shake of the head. He had tried Lagos University Teaching Hospital when he gallantly fought off a stroke in 2008. Cairo must be infinitely better. People shook their heads when in 2006 he rendered a certain confused speech. He said he could have overthrown Obasanjo. But chose not to. He said he didn’t know why northern youths in major Mustapha and co. were languishing in prison for mere attempted murder.

Malu was a good man. He was a patriot. He was a soldier’s soldier, in the words of David Mark. Good obituarists don’t write all they can. The memory of the dead must be left in fine scents.

Adieu General Victor Malu. You did your best.