Tinubu’s budget arithmetic, drums and KWAM 1

By FESTUS ADEDAYO

(Published by the Sunday Tribune, March 31, 2024)

“I know the arithmetic of the budget and the numbers that I brought to the National Assembly, and I know what numbers came back… Those who are talking about malicious embellishment in the budget; they did not understand the arithmetic and did not refer to the baseline of what I brought,” President Bola Tinubu declared at the State House, upper Friday. And there was ominous quiet on the home front. He was hosting the leadership of the Senate at the breaking of Ramadan fast. Do you remember the fuss generated a couple of weeks ago by the allegation of N3.7 billion budget-padding leveled against the senate by Senator Abdul Ningi? Its most fitting description is the relations between the cattle and the egret. While some Nigerians worry that Tinubu was offering presidential shield to parliamentary fraud, the anecdote of cattle and egret best explains it. It is an Aso Rock cattle and National Assembly egret, both in dalliance for self survival. Hapless Nigerian people had nothing to do with it.

Except on a closer scrutiny, it may be difficult to explain the odd alliance between cattle egret and the cattle. The cattle egret is a famous bird which feeds on ticks and flies. It is a parasite on cattle. Often found taking shelter on their back, feeding fat pecking ticks off their skin, the alliance between these strange fellows is for the sake of self. Egrets get their daily meal by helping the cattle take away their discomfort. They reduce the number of flies on the cattle’s body. The cattle could, in anger, flick their horns or tails to haunt the egret to death for the audacity of climbing their back. The cattle however allow the egret endless stuffing of its guts with their tick irritants. And there is mutual satisfaction. So, when Tinubu said, “Thank you very much… But your integrity is intact,” you would imagine the cattle speaking at an Iftar gathering of cattle egrets.

Tinubu put a final wedge on the controversy last week. With statistics? No. He flung his self-acclaimed knowledge of arithmetic, ostensibly as an accountant. What is the recency of the president’s knowledge of accounting and arithmetic? Comparing his’ with, for instance, Seun Onigbinde of BudgIt’s, who statistically confirmed the padding allegation, our president’s may be rusty arithmetic. Not to worry. With that smooth presidential assent, the president, a man of integrity who recently celebrated an iconic 72nd birthday on earth, removed his age-long and highly acclaimed apparel of integrity and wore it on each of the 109 senators. Now that the president has thus pronounced, our Senate now wears angelic, cocaine-white apparel. Onigbinde had said: “TETFUND should not just get an allocation. What are you spending money on? INEC is collecting a huge chunk of funds but there is no public details about what the funds are used for. If you put all these together, that is around N3.5 trillion to N3.7 trillion. So, if Ningi wants to interrogate that there are components of the budget where there are no breakdown, that is very factual.”

Don’t mind Onigbinde. The president’s arithmetic is hippopotamus-sized. The trillions of Naira allegedly padded have received their lost integrity. Senate President Godswill Akpabio’s N90 billion constituency projects inserted into the budget have become angelic. They have shed their quills of fraud and self-centeredness, a la the president. The N500 million Opeyemi Bamidele confirmed “ranking” senators got infused into the budget, totaling N17billion, has removed its sleaze waistcoat feathers. The president, a man of highly burnished morality, is happy. The senate is glad. Nigeria is moving on regardless, even if you insist it is on wobbly legs.

On this Mount, today is however not a day for arithmetic. Not a day for fraud arithmetic. It is a day for birds, singing and drumming birds. While the president flaunts his arithmetic knowledge, let us flaunt biology. The biology of birds. Do you remember what that irritable American ex-president, Donald Trump, once called quid pro quo? In the Nigerian lingo, it is better rendered as, You Rub My Back, I Rub Your Back. It is benefitting the need of one without posing any noticeable risk to the other. When you carry a shameful swarm of ticks and ants on your back like the Tinubu presidency does, you need Akpabio’s cattle egrets to feed fat on them for your peace.

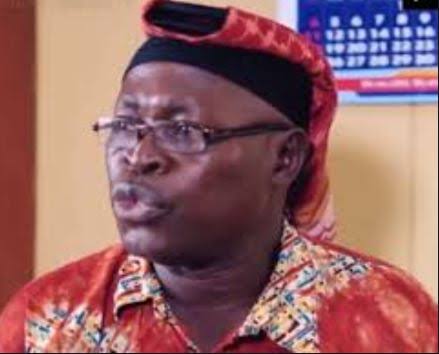

Sorry, I digressed. Rather than peer further light into Tinubu’s vacant, Rub My Back, I Rub Your Back, Paddy Paddy budgetary arithmetic, I elect to veer into society today. The social schism among Nigerian singers and drummers particularly bothers me. Most likely due to my biographical work on a Yoruba Apala music lord, Ayinla Omowura, I have received several calls to do a review of the recent back-and-forth accusations and allegations between Yoruba Fuji musician, Wasiu Ayinde, also known as KWAM 1 and his erstwhile lead drummer, Kunle Ayanlowo. My work, entitled Ayinla Omowura: Life And Times Of An Apala Legend (2020), dwelled tangentially on the crisis in Omowura’s musical group – between him and his drummers, and his band manager, Bayewumi, who eventually killed him. This recent musical ruckus was shot to the zenith of discourse, especially in the southwestern part of Nigeria, by Ayanlowo. The drummer had complained that in decades of drumming under the Fuji musician, KWAM 1 fed his guts the fattest gains from the organization’s huge takings, leaving him in the cold. The musician debunked the claim. Without drummers, Ayanlowo submitted, musicians are in the cold. This is true.

This is leading me right into a short history of drumming and singing which tear singers and drummers asunder. Àyángalú is known to be the progenitor of drummers, the deity spirit of the drum. It is drummers’ guardian spirit. In one of his SOS calls in the social media against KWAM 1, Ayanlowo brought out a drum as witness to his allegation against his former boss, asking Àyángalú, the twine that solders them together, rather than the Bible or Quran, to judge between them. This is a recognition of the spiritual potency of drums and the abiding spirit of Àyángalú who is often symbolically acknowledged and represented in drums. For instance, out of all the ensemble of drums, the one called Gudugudu, with a pot-like shape, represents the sacred symbol and spirit of Àyángalú. When going out for major performances, an appeasement and invocation of the guardian spirit of Àyángalú is often done. Drummers pour libations, mostly of dry gin alcohol, on their drums, with prayers to the spirit of Àyángalú to wear them like garment.

Music is as old as the Yoruba society. The Yoruba music world is a complete confetti of drum, song, chant and dance. In the Yoruba world of music, drums and musical instruments deployed for melodious rhythms and tones acted as bridge between humans and different deities called Orisa. They constituted the age-long rituals with which society communicated directly with their deities. There is no way the concourse between spirituality and ritual performances can be discussed without the agency of traditional drumming and singing. Drummers and musicians played mediatory roles in meeting the spiritual and the social needs of the communities where they lived. They invoke deities to provide assistance and guidance to their earthly worshippers. Both singing and drumming were thus traditionally perceived as sacrifices to the Orisa. When the deities were sufficiently roused up by enthralling songs, they got thrilled enough to intervene in the people’s individual lives. The mystical and supernatural nature of drums is demonstrated in that, if the hearts of a warring party is as hard as stone, drumbeats tenderize them like flesh. In the heat of fierce battles, a drummer only needs to drum the eulogy of the warriors and an armistice is procured. It was why they followed warriors to the front.

The Àyàn family is reputed to be the family of drummers. Àyàn is the family that produces assorted sorts of Yorùbá drums. To keep the family tree intact, animals are killed by members, their skins tanned for the preparation of drums. They also prepare generations to come for drumming. In the olden days, the Àyàn family went to war with warriors, showering eulogies on the fighters, chanting and invoking their praise poetry. This spurred them into victory. During the wedding of Àyàn daughters, a special memento of a specialized Dùǹdún drum, festooned with tiny bells called Saworoidẹ, is given to them as gift by the Àyàn family.

Before KWAM 1’s Ayanlowo, many Yoruba made fame out of their drumming craft. One of such was Shittu Ọ̀kánjúà, a drummer of the late Atáọjà of Osogbo, Oba Adénlé; Babátúndé Ọlátúnjí. The list also includes Ọba Adetoyese Láoyè, the late Timì of Ẹdẹ, in Osun State who, with his scintillating drumming of the Dùǹdún drum, produced the renowned signature tune of the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Station.

By either happenstance, location in history or abiding connection with Ayangalu, forefather of drum ancestry, Ibarapa people of Oyo State constitute the highest number of drummers in history. Ranging from Ramoni Adewole Alao, a.k.a. Oniluola, (said to have migrated to Abeokuta from Idere in Ibarapa Central Local Government) Alhaji Mutiu Jimoh, a.k.a. Mutiu Kekere (Ebenezer Obey’s drummer, who hailed from Idere) to even Ayanlowo, who is a major cast in what has become drummers’ eventual tiff with their musician bosses, the list of Ibarapa drummers who helped traditional musicians to stardom is endless. Other famous musicians who also eventually had issues with their singing bosses were Kamoru Ayansola (Sikiru Ayinde Barrister); Orikanbody Ayanwale, who drummed for Kollington Ayinla; Aromasodun, who also drummed for KWAM 1; Rafiu Ojubanire (Haruna Ishola) and Shittu Shitta Alabi, the drummer of Yesufu Kelani who slumped and died on stage in 1972, drum in his hands. Recall Kelani’s elegy to Alabi entitled “Iku O Mo Olowo” – death is no respecter of wealth.

Drumming was more revered than singing by the deities because it provided links between the supernatural and the physical world. Entertainment came only as a latter function of drums and singing. So, aside being used for communication purpose, mourning, praise-singing, declaration of hostility and sober reflections, each drum and drumming indicate what they communicate. The different drums like Gángan, the talking drum; Ìyá Ilù; Dùndún; Ómèlè; Bátà and the Ṣẹ̀kẹ̀rẹ̀ were all totems of different gods, each of which was associated with a drum. Cylindrical drums like Ìgbin, Ìpèsè and Ógidàn bore paternities with individual Orisa, spirit or deity. While the Ìgbin drum has causal link to the snail called Ìgbín by the Yoruba, the deity’s paternity it bore was Ọbàtálá, arch-divinity associated with procreation. Ìpèsè drum was a ritual performance for the deity Ọ̀rúnmìlà and Ogidan drums were solely for the veneration of Ogun, the god of iron. Ìgbin was made with the skin or dermis of the deer called Ìgalà. Till today, in the Èjìgbò area of Ọ̀yọ́ State, the Ìgbìn drum is still the totem of worship of Ọbàtálá during the people’s New Yam Festival. The Bembẹ̀ ̣ drum on its own is peculiarly beaten with hands and not sticks, accompanied by two bells and has as its totem, the worship of the river goddess of Ọ̀ṣun and Ọya. The Àshíkò drum, a cylindrical and tapered drum, made of hardwood and goatskin hide, is also used during festivals. Other drums were Agidigbo, Osán, Sákárà, Gúdú Gúdú, Gbèdu etc.

Drums and drummers maintained their superiority until the late 1960s in Yorubaland. Their hold however began to wane when drums ceased being primarily agencies of ritual spiritual performances. During this time, drummers were kings as virtually everyone not only enjoyed the rhythm they produced but could access the words communicated with their drum sticks. During my research, I spoke with drummers like Adewole Alao, lead drummer to Ayinla Omowura, who told me of how he had acquired quite formidable following before his fans asked him to look for a singer to accompany his drumming rhythms. Adewole thus told me he had to scurry almost the entire Abeokuta city before he found the melodious-voiced Ayinla. They had hardly been together for a decade before fight for superiority tore them apart. Adewole went his way, while Omowura picked another drummer named Adenekan, a.k.a. Yebere, who was principally apprenticed as a barber but who drummed for leisure. Ayinla was together with Yebere until another tiff spiraled among them, which led to the return of Adewole to the musical fold.

In one of his live plays, Omowura, who was killed during a scuffle in 1980, sang a song which will seem to capture the disagreements that occur between musicians, their drummers and even band organizations in general. In the song, he provided the allegory of an imaginary husband who gave his wife money to prepare a bowl of soup. When the soup was ready and a plate of accompanying eba was placed before him, the husband removed his clothes and fled the house. The lyrics goes thus in Yoruba, “K’eyan o f’owo obe si’le o/K’obe wa jina/ k’an gb’eba sí’le, k’o f’ere ge…” He sang the song when Bayewumi, the man who was to later stab him to death, decided to pull out of the band. In the song, Omowura likened Bayewumi’s abrupt pull-out to one who had invested immensely in a cause but when it was time to reap its fruits, amazingly, of his own volition, fled the pot of honey.

When asked what led to the disagreement between him and Omowura, just like in the KWAM 1 and Ayanlowo case, Adewole put it to sharing of proceeds of their musical sweats. In virtually all the scuffles among musicians and their drummers, this has always been the case. In 2019, when I got to Adewole’s house in Abeokuta, I was more than shocked. It was barely habitable for any human being. He had no presentable chairs for guests to sit on. Noticing my discomfort, the old man burst into tears, amid sobbing, “Se bi ile gbajumo se ye ko ri niyi?,” meaning, “Is this how a socialite’s house is supposed to be?”

So, why do drummers always engage in a tango with their singer counterparts? Sometimes in the late 1970s, billed for a recording at the EMI studio in Lagos, Omowura was shocked to discover that all his drummers and backup vocalists suddenly disappeared. The bus that went to their individual homes could not see any of them. It was like the trade dispute of today. They alleged that he was short-circuiting them from the takings of the band. Ibadan drummer, Alamu Tatalo also had a dispute with Amuda Agboluaje, the vocalist he recruited, leading to a bitter rivalry that was never sorted out till both died. So also did Awurebe exponent, Dauda Akanmu Ade-Eyo, a.k.a. Epo Akara who had a bitter feud with his drummer, Alhaji Lalere.

Why do virtually all drummers live in penury? Why don’t they harvest the fruits of stardom like singers? The truth is that both singing and drumming are beggarly vocations, from time immemorial. This may thus not be unconnected with the poverty-stricken fate that comes their way. Anyway, some of them maintain that the singers are not in the real sense their bosses; that each of the musical ensemble, to which drumming is one, is a critical component that makes the musical medley. When I asked Adewole why he left the Omowura group, he said the Apala lord turned him, the boss, to a servant – “o so oga d’omo ise.” I submit that contemporary crises among musicians are a resurfacing of the ancient rivalry that has always existed between drummers and singers and battle for supremacy between drums and songs. Does standing in the front as lead vocalist make the singer the leader? This was the question that the Jamaican Wailing Wailers, the musical triumvirate of Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Neville O’Riley Livingston also confronted in the early 1970s. When Briton Christ Blackwell of Island Records, on a UK tour he organized for the group, announced to the British audience that the group was Bob Marley & The Wailers, rather than a trio among whom rotated lead singing of tracks, the road to the eventual disintegration of the group was already paved.

Illiteracy, the challenged beginning of most drummers and the violence-ridden nature of music, especially traditional music, are the roots of confrontations that often occur between singers and drummers. The way out is insistence on legal agreements and representation by all the parties. This will spell out the terms of their engagement. In this way, frictions will be reduced among these men and women who soothe our souls with melodious music.